A Quest for Taste in Zero Gravity

Food is an essential part of an astronaut’s life in space. Beyond providing the caloric and nutritional needs necessary for health and performance, food plays an important psychological and social role, becoming a comforting and familiar reminder of life on Earth.

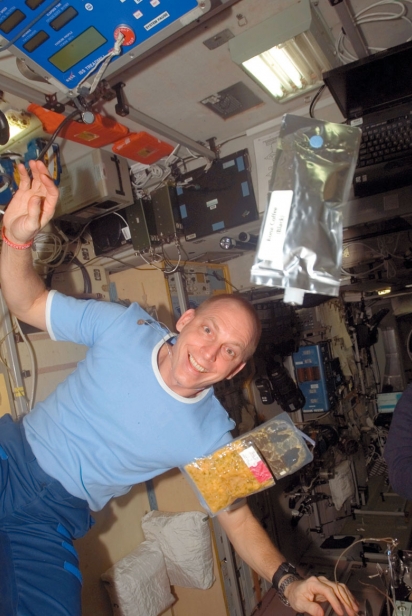

“I spent most of my time in space with two Russians and to me one of the most psychologically positive aspects of my five months in space was the fact that we ate every single meal together. That camaraderie and that sense of family was hugely important, the food notwithstanding,” said Clay Anderson, a retired astronaut who worked aboard the International Space Station in 2007.

When we earthlings eat, we have choices and the freedom to prepare what we want to eat. We can experience the aromas of a pot of food cooking, sit down at the table and look at the food presented on a plate. That’s not the case in space, where foods are eaten out of pouches and plastic packages, and factors such as fluid shifts in the body caused by weightlessness, a closed environment and competing aromas can influence how food tastes.

This makes the job of providing astronauts with a variety of high-quality, flavorful food ever more important, especially now that they spend months aboard the ISS and NASA is looking at long-duration missions to Mars. The people charged with feeding the crews are right here in Houston at NASA’s Space Food Systems Laboratory.

“When we were just flying Shuttle missions, very few crew members cared about the food that much,” said food lab manager Vickie Kloeris. “They thought, ‘Ah, it’s a week or two; it’s like a camping trip so we can find something we like,’ but when you’re up there a long time, food takes on a much bigger importance.”

Beyond tubes and cubes

The food astronauts eat today has come a long way since the early Mercury program when John Glenn, the first American to eat in space, ate applesauce out of a tube in 1962. Crews aboard the ISS can choose from some 200 foods and drinks processed and packaged at NASA’s food lab. Dishes are familiar foods, such as shrimp cocktail, mac ’n’ cheese and beef fajitas. Drinks include anything from apple cider to milk to coffee. Astronauts can also enjoy commercially available foods such as nuts and granola bars in their familiar form.

There is no refrigeration in space so foods are either freeze dried or thermostabilized, which is essentially canning except NASA packages the foods in pouches much like those used for MREs in the military.

For expeditions, NASA sends a standard menu of foods packed by category — entrees, sides, vegetables, snacks, desserts — that rotates every eight days; the crew can pick what they want to eat at each meal from those choices. Sometimes they get a little creative.

Anderson recalls a Space Station crew making a “cheeseburger in paradise” when Jimmy Buffett visited mission control by using rehydrated beef patties, cheese paste and a tortilla. (Tortillas are astronauts’ bread since bread produces crumbs that will float.)

Even when the food is good, having choices can make eating in space more pleasant. To afford astronauts a little more variety, NASA allows them nine crew-specific containers for their six-month stay in which they can choose to send more of the dishes on the standard menu or commercially available products that meet NASA’s requirements. The food lab also sends fresh foods, such as fruit or ice cream, as an occasional treat if there’s room in the cargo ships that resupply the station.

Overall, this food system has worked well for the ISS so the food lab doesn’t do much menu development for the station anymore. The focus now is on extending the shelf life of food to five or more years while ensuring it meets nutritional requirements and retains an acceptable quality and taste.

Next stop: Mars

Missions to Mars are expected to last two to three years but sending the food with the crew would be an issue due to its weight. “If the engineers had their way we’d send all pills,” says Kloeris, “but the human body needs real food”. Food then would have to be prepositioned for the crew and remain stable throughout their stay and flight back to Earth.

While NASA’s food lab has the ability to make foods that last five years from a microbiological standpoint, the food lab can’t control the chemical changes that will occur in food over that long period of time.

“Flavor, texture, color and nutritional content are going to change and not for the better, so how can we extend the shelf life and still have good-quality food that they’re going to want to eat and still have nutritional value?” said Kloeris.

To this end, NASA is looking at combining food processing technologies such as high-pressure processing and microwave sterilization with lower ambient temperature. High-pressure processing is a cold pasteurization technique that uses high pressure to deactivate microorganisms and enzymes. Because food is exposed to less heat, in theory, it will yield a higher quality product that will take longer to reach that unacceptable point of degradation. With microwave sterilization, heat is applied to foods but for shorter periods of time.

Food scientists are also studying nutrient degradation. Vitamin C, for instance, depletes very quickly over time but NASA has found that it’s very stable in powdered beverages enriched with it. “It could be that for Mars, there’s a prescription of vitamin C-enriched drinks,” said Kloeris.

To study psychological factors, the food lab partnered with NASA’s Human Exploration Research Analog, a ground-based chamber at the Johnson Space Center where NASA holds psychological studies, to look at food issues, including how much variety humans really need to stay interested in eating. Military studies have found that limited food choices lead to menu fatigue. When menu fatigue sets in, soldiers start eating enough to survive but not to thrive. That wouldn’t work for NASA.

“We want our astronauts to be high performing throughout the mission,” said Kloeris, “even on the return trip.”

At this point, we may have more questions than answers about the food that will support a mission to Mars. What’s certain is that food is as important to humans in space as it is on Earth and Houston will play a role in uncovering the best way to nourish the first travelers to deep space.