From Scraps to Scrumptious - Three Local Chefs Help us to Waste Nothing

In his restaurant kitchen at Oxheart, Chef Justin Yu tries to use the most out of every ingredient that comes into his kitchen. A dessert on his menu last fall paired frozen yogurt with the whole apple: its flesh poached and pickled, its skins dried and its cores used to make apple butter. It’s an example of how Chef Yu prepares different parts of an ingredient in ways that add unique flavors and textures to a dish, all while wasting the least amount possible.

“While it’s great to save the money and you feel great about it, it’s recognizing the work that someone put into growing something,” he said. “You’re not throwing it all away.”

Home cooks could learn something from Chef Yu. Roughly 40% of food produced in the United States goes to waste, with the average American throwing away 20 pounds of food per month, according to the National Resources Defense Council. In addition to wasting the water, energy, labor and money it took to produce, this food ends up sitting in landfills, creating harmful greenhouse emissions.

Consumers alone can’t resolve this growing issue, but there are things they can do to help: plan better, store foods properly, learn how to know when food goes bad, buy imperfect produce and cook and serve less food. They can also learn to prepare what they would usually trash—think stems, tops and roots. It may seem daunting and time consuming but it doesn’t have to be.

“It can be as simple as putting something on a cookie sheet [to dry] overnight at 180°,” says Chef Yu.

Stems, for example, are usually the most flavorful part of the plant. Adding cilantro and parsley stems to marinades and vinaigrettes is easy enough for someone to do at home. Or, Chef Yu says, add the chopped stems and a little olive oil to cooked quinoa for a quick snack or light lunch.

BACK TO BASICS

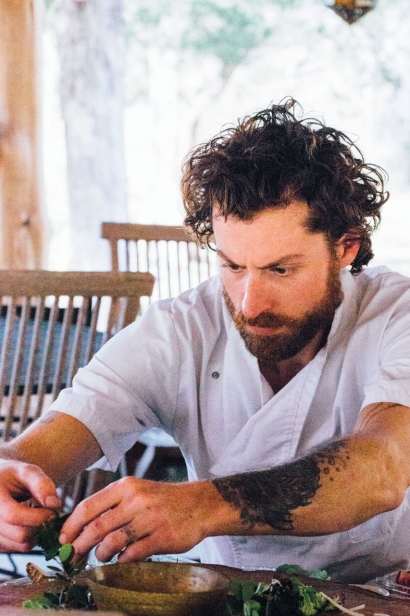

In some ways learning how to use food scraps is a refresher course in cooking. Chef Chandler Rothbard of Animal Farm, a farm in Cat Spring that runs a community-supported agriculture (CSA) harvest subscription program and supplies many of Houston’s restaurants, suggests learning the ba-sics. By knowing how to grill, sauté, braise, steam and roast, it’s easier to think about what to do with an ingredient.

So is having a little forethought. Chef Soren Pedersen runs a local catering company and is often at the Urban Harvest’s Eastside Farmers Market showing people how to cook. To get an idea of the kitchen scraps we tend to throw away, Chef Pedersen suggests collecting them in a container: “I think people would be surprised by what they’re throwing away,” he says. “Add that up day by day, year by year.”

Chef Pedersen recognizes that time is often the enemy of home cooking, but with a little planning anyone can prepare meals in a pinch. Soups and stocks are easy, and perhaps obvious, dishes to use up scraps—you can throw just about anything into them, and once made, they can be frozen into small portions and used for future meals. Chef Rothbard suggests using stock to cook rice, as a base for a soup, as a soup itself or in purées to add or intensify flavors. Fresh herb purées and pesto are also great to have on hand and can be prepared with just about any herb or vegetable. Use them to sauté vegetables, marinate chicken or season fish. Or add scraps, such as tops and stems, to your raw salads.

In his kitchen at Animal Farm, Chef Rothbard demonstrated how to prepare several dishes using many of the same vegetables in a short amount of time. Have broccoli? Use the stems and florets for a soup and set the leaves aside for a stock and pesto. Cilantro? Throw the stems into your stock and use the leaves for pesto. Carrots? Use the whole vegetable, tops included, in stock. Spring onions? Use the whites in your soup and save the greens for your stock. Chef Rothbard typically re-plants the roots, but Chef Yu says you can also wash them really well and pickle them for an intense onion flavor.

PICKLE, FERMENT, DRY

Old preservation methods such as pickling, fermenting and drying, are also great tools for reducing kitchen waste, as pretty much any fruit or vegetable can be preserved using them.

At Oxheart, vegetable trim is salted and fermented into sauerkraut that then serves as a base for other dishes. The whites of spring onions or green garlic, for example, can be cooked and pickled, while the greens, which Chef Yu says people commonly throw away because they find them fi-brous, can be sliced and fermented to make them a bit more palatable. Onion tops can also be dried and infused into oil and then served as dressing for a roasted whole onion.

Using these methods adds layers of flavor that people may not be used to, Chef Yu says, you’re using the value of the work that goes into growing food rather than just picking the best part of an ingredient and throwing the rest away.

THINK IN FLAVORS

Chefs would seem to have an advantage over home cooks when it comes to preparing scraps. Yet by changing the way we think about the food we cook, we can train ourselves to know what to do with them.

Look at scraps as flavors rather than flawed parts of a fruit or vegetable, Chef Yu says. If you have a bitter part, well, bitter is a flavor that can counterbalance something sweet. While almost all plants can be used entirely, not everything is equally palatable. The key is to taste and try.

By doing so, home cooks can become more intuitive and get to the point where they work with combinations of flavors rather than structured recipes, says Chef Pedersen. This in turn can make cooking a lot quicker, more effortless, fun—and much less wasteful.