A Royal Gumbo

I grew up believing I belonged to a royal family: the Cheneverts (pronounced “shih nuh vehr” in French, which I liked to tell everyone who didn’t ask) of Barrett Station, Texas. I learned of my royal heritage when I was 6 years old, after my cousins and I got into a fistfight with a group of out-of-towners at the local park. The fight started over territory. My cousins and I claimed the park for a game of hide-and-seek that day; no one else could join or play at the park until we were done. Forgive us—royalty made us bratty. One insult led to another and a brawl broke out. Kicking, punching, biting, yo-mammajokes—the works. A lady ran toward us to break up the fight. After a stern lecture, she demanded the names of our parents. We told her we were Kenneth Chenevert’s grandkids and, just like that, we were absolved of any blame. She didn’t care who started the fight. She sent the out-of-towners away and drove us home in her Caddy; she didn’t even tell our parents about the fight. That changed our group of deviants into an army of tyrants. We picked fights, crashed parties, and shamelessly accepted freebies from the corner stores.

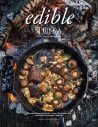

My grandfather earned his family’s title through two avenues: food and religion. He was an artist when it came to crafting meals, some of which were traditional Cajun dishes while others were original concoctions thrown together with what he had and then named so he couldn’t forget how he made them, like Okra, Sausage & Shrimp with rice. He earned a reputation in Barrett Station by working with and feeding the community. He had a second kitchen attached to his house, where he would do most of his cooking with the windows and doors wide open. Homemade boudin and chitterlings lined the countertops, gumbo stewed on the stove, oxtails braised in a skillet. Neighbors, relatives, and strangers would wander towards the smells coming from that second kitchen. They’d poke their heads in, make small talk, and often leave with to-go boxes. No one was ever disappointed.

My grandfather had a big heart and devoted his life to family and the Barrett Station community. Before marrying my grandmother, he had planned to complete seminary school and become a Catholic priest. Naturally, plans changed. Some Barrett Station locals—and even we grandkids—speculated that catering to the community was my grandfather’s way of paying his debt to God. We believed our grandfather inherited a curse for abandoning priesthood. That curse manifested in the deaths of three children—one after the other—until he passed away from a heart attack. Some of my most vivid memories in Barrett involve deaths and the gatherings we held in the aftermath of those deaths. I remember my family in black, faces raw with tears, and bowls of gumbo. Gumbo was and is the staple dish for all family gatherings. We consume it on holidays, death days, and cold days. And though gumbo can taste like Christmas to me one day, it can taste like death on another.

I consider myself a gumbo snob because of my grandfather. He made it best. Every time I eat out at a Cajun restaurant, I try the gumbo—and almost always, I’m disappointed. There is a magic to the way my grandfather made gumbo—very few people can replicate it. My dad might be the lone survivor of the gumbo arts, with my aunt being a close second. Of course, this could all be up to preference. I was raised to believe okra in gumbo was culinary blasphemy. Yet, many establishments add okra to their gumbo—and I still find it to be slimy and distasteful. Some add the chicken to the broth too soon, causing it to shred and blend with the other ingredients. Others add tomato sauce to the broth—unarguable blasphemy. And some places struggle to find the balance between roux and broth. Too much roux gives the gumbo the consistency of gravy, while too little takes away the smokiness of the flavor and leaves the broth watery. I like gumbo somewhere in the middle—more like a stew—which is the way my grandfather made it and the way my father makes it today.

Food and memory have always fascinated me. I devoted my undergraduate and now my graduate studies to exploring that relationship and the stories that can be told from them. For me, gumbo is the flavor of my family. It’s the dish that has continually brought us together, for celebrations and for mourning. Part of my royal heritage was built on my grandfather’s gumbo and its ability to unite people. His recipe is challenging to duplicate because he never measured; he just sprinkled and poured as he felt necessary. So, I—and others who follow him—do the same. Mastering his gumbo technique allows us to continue his tradition of uniting strangers through food. And, in a way, continue paying his debt in his absence.