Spirits on Oak - What a Difference a Barrel Makes

Smooth Operator: Charred barrel creates a whole new dimension

“Skål!”—“cheers” in several Scandinavian languages—not only sounds ominously similar to skull: Myth has it that the word (meaning: bowl) came from a Viking tradition of drinking from your enemy’s skull as a toast to the battlefield success.

A skull is not what Michael Griffins will use to pour his handcrafted aquavit—although he did name his spice-infused spirit after the Norse mythology’s banquet hall for slain warriors: Valhalla, the “hall of the fallen.”

Aquavit (also spelled akvavit) is a high-percentage alcohol (at least 37.5% infused with spice.) According to EU regulations the main spice in aquavit (distilled in Northern Europe since the 15th century) should be caraway and/or fennel seed. Either way, Griffins won’t divulge the spices used for his Valhalla Aquavit.

Introduced to the spirit through Scandinavian friends in Katy—Houston has a large Scandinavian community—Griffins started making aquavit in his home kitchen and began barrel-aging when his wife gave him a small oak barrel for Christmas.

“The unoaked, unbarreled batch was more two-dimensional,” he says. “Adding oak, you add another dimension to it. It changes the flavor profile, the feel on the tongue, everything. It refines it, brings depth to it, makes it more interesting.”

In need of a commercial space when Valhalla took off, he now operates from Yellow Rose Distilling, where each batch matures in two 58-gallon Hungarian oak barrels. The entire production is done at the distillery, from infusing the alcohol with the spices in his own soaking tanks to barreling, filtering and, ultimately, bottling.

While Griffins uses a distilled spirit to make Valhalla Aquavit, the whiskeys made at Yellow Rose Distilling originate in the grain room on the premises: Organic corn from the Panhandle is used for the Outlaw Bourbon, rye from the Midwest for the Straight Rye Whiskey and the malted barley for single-malt whiskey is imported from the UK.

All grains are ground onsite and cooked with water to turn the starches into sugar. The mash then goes into the fermentation tanks, where whiskey yeast is added to consume the sugars. After three to seven days the fermented mash is pumped into the still. As the still is gradually heated, the mash starts to boil. The alcohol evaporates, cools down and is collected in the condenser. After this first run (or the stripping run), the alcohol goes back into the still for a second run. This run—the spirits run—separates the good from the bad alcohol, or in distiller terms: the heads, hearts and tails. The hearts is the good alcohol that goes into the barrel. The leftover mash finds its way to a local cattle farmer in East Texas and a farmer in Beaumont who feeds it to the pigs.

The obtained distillate is clear as water and flavored only by the grain used. “It gets all of its color and a lot of its flavor from the barrel,” says Troy Smith, co-owner and distiller at Yellow Rose Distilling. He adds that the 140 proof is diluted to maximum 125 proof before it goes into the barrel, where it mellows further down to about 92 proof (46%) for bourbon, 90 proof (45%) for rye whiskey and 80 proof (40%) for single malt. Bourbon, by law, must be aged in new charred American oak barrels. Holding up a jar of clear, high-proof 100% corn whiskey, Smith says: “Once it goes into that new charred American oak barrel, it’s bourbon.”

CHEMISTRY

Charred oak is what gives whiskey that smooth finish, smoky notes and hints of caramel, vanilla and other spice. Oak wood contains many organic compounds, some of which have an essential impact on alcohol when it comes into contact with oak. The main reason for charring (exposing oak to high heat) is to encourage those compounds to release wood sugars, aromas (vanilla/spice) and mellow oak tannins. There are many different kinds of oak, with American oak said to impart the most intense flavor.

While bourbon is bottled from the first barrel, single-malt whiskey made at Yellow Rose Distillery is double-aged: after aging on bourbon barrels, it is transferred to finish in toasted port barrels. Smith pours us a comparison tasting of single malt whiskey, one from the bourbon barrel—that I would be happy to take home—and one from the port barrel. And in the latter, the sweet fruity notes deepening the whiskey’s diverse flavor profile convince that finishing in a port barrel makes a good whiskey even better.

A BARREL ROLLS INTO A BAR

As the matured bourbon leaves the barrel, the barrel itself finds another destination: It rolls into a bar to lend the aromas and sugars of its charred interior—now enriched with residual flavors of bourbon—to mature cocktails.

Late on a hot Monday afternoon in July, I walk into a bar to talk about maturing cocktails on oak with Mike Raymond. He is the owner of Reserve 101, whiskey bar on the corner of Carolina and Dallas in east downtown (EaDo) Houston. About five years ago, he started to barrel age Manhattan cocktails (the classic mixes whiskey, sweet Vermouth and bitters) and now has five different cocktails on the menu, including Manhattan, Negroni and Boulevardier.

Rather than explain to me what maturation in a bourbon barrel does to a Manhattan, he pours one of each. The aged cocktail is lighter in color, is mellower in flavor and has a very smooth finish. In contrast, the un-aged Manhattan is bolder. What stands out most, though, is the thicker viscosity in the aged cocktail.

“In our Manhattan we use maraschino liqueur. It gives it sweetness and a velvety mouthfeel. But when you put it in a barrel, that liqueur is turning into a syrup.” Raymond says it isn’t exact science but there are many elements to consider when you put a cocktail on oak to mature: the ratio of sweet liqueur versus bitters, the kind of spirit used and the level of proof and clarity. Vermouth adds a measure of acidity and on oak—thanks to the porous nature of wood some air does get in—there is a degree of oxidation. Good oxidation adds pleasant, fruity notes. Bad oxidation makes a drink harsh.

The barrel itself becomes a variable, losing its oaky influence after several uses. Even the temperature where the barrel is kept plays its own part in the aging process: When it is warm, spirit soaks well into the wood. “In a perfect world I would put them on the roof and let the sun beat down on them. But you get very high evaporation rates. And of course you have to worry about the weather and other things,” says Raymond, who warns to not use any citrus (will render your cocktail putrid) or dairy (will go off) when aging a cocktail on oak.

This summer he is experimenting with clear spirits and has a Sazarac maturing, for which he used a clear rye whiskey that never aged in a barrel, and absinthe from Tenneyson Absinthe Royale in Austin. The Sazarac would probably be ready in September or October, he said.

After four to six months, the aged cocktail is drained from the barrel and bottled in seven-ounce bottles, or the equivalent of two to three drinks. “It’s like miniature bottle service.”

> Yellow Rose Distilling offers tours and has a tasting room. Check the website for more information. Valhalla can be purchased at Tony K’s Home of Fine Spirits: 2720 Bissonnet St, Houston

DIY BARREL MATURATION

In Pearland, Deep South Barrels has miniature charred barrels for the home-brewer or anyone who wants to try out aging alcohol on oak. They offer them in four sizes: one-, two-, three- and five-liter. “We call them “drink, drunk, shit-faced and passed-out,” says Randall Bentley, founding partner and owner of Deep South Barrels. “And you can customize them whichever way you want.”

The on-site branding machine takes care of that customized look. The barrels have a medium char (level three), which is achieved by putting the barrel into a container. A fire is built with wood shavings and thrown into the open barrel, which is rolled and moved around until the insides slowly become charred. Bentley takes one of his barrels apart for us to take a look.

“There is no glue. It is the wood that swells the barrel shut when it gets wet. A real barrel has no glue: Glue will taint the alcohol.” Aside from oak barrels, Deep South further helps the DIY barrelager with recipes using Maker’s Mark (a Kentucky bourbon) and a wide variety of essences to flavor your home-aged spirit.

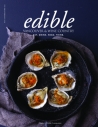

Deep South Barrels are available from Specs, among others. The photo gracing our Sept/Oct 2016 cover shows a selection of Deep South Barrels.