On a Mission to Upgrade School Lunches at HISD

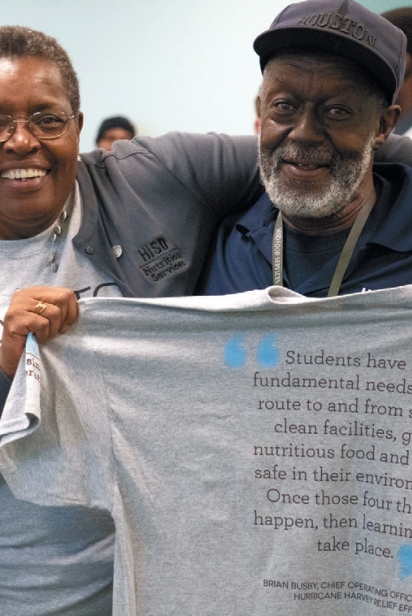

Betti Wiggins is on a mission to bring good food to every student in the Houston Independent School District—she’s even got T-shirts. As HISD’s officer of nutrition services, Wiggins is always looking for new ways to innovate and connect her students more deeply to the food they eat. Did you know there is a family-style lunch service for the pre-K classes at Garden Oaks Montessori? Or that HISD is planning a new agricultural education center? Or that HISD is working to offer dishes that reflect Houston’s diverse student body?

“I firmly believe that kids should have more than a consumer relationship with their food,” said Wiggins. “You can only do that if you get them engaged in the process.”

Before coming to Houston, Wiggins was known for her ability to work real, practical magic as an innovator in Detroit public schools. It’s not easy to make changes on little to no money while moving within the many constraints of the federally regulated National School Lunch Program (NSLP), and Wiggins knew “innovation” would look different here than it did in Michigan.

“I came to Houston hoping to right this ship in the best interest of kids,” said Wiggins. “I wanted to turn the program back over to the community, to start working for stakeholders and not shareholders.” Out went the management company that had been serving HISD lunches; Wiggins brought production back in-house, focusing resources on improving meal quality and food education for students.

Family-Style: the Right Fit for Little Ones

At Garden Oaks Montessori school, lunch for pre-kindergarten students is served family-style in the classroom every day. After a campus renovation project required temporary, direct-to-classroom lunch delivery, school staff quickly realized this temporary fix could provide a permanent solution for their youngest students, who faced a very long walk to and from the campus cafeteria.

“I pretended I was a 4-year-old and I took that seven-minute walk,” said Wiggins. “They were off in a corner, with a long way to go to eat. Serving them in the classroom just made more sense.”

Imagine being 4 or 5 years old and it’s time for lunch. Your lunch period at Garden Oaks Montessori is a (relatively generous) 30 minutes. You line up at the door with your friends and take the seven-minute walk to the cafeteria, then you wait in line for your lunch. Next, you find a seat and eat while you talk with your friends. Maybe you have lost a tooth or two. And don’t forget you have to clean up and return your tray. How much food do you think you’ll have time to consume in that time frame? Keeping pre-K students in the classroom for lunch at Garden Oaks Montessori is less chaotic and gives kids more time to connect to their food—and each other. Garden Oaks Montessori principal Dr. Lindsay Pollack credits Wiggins with being open to seeing the value in the classroom lunch program.

“Family-style lunch in the classroom is a perfect fit for Montessori, and when Betti came and was open to it we were ready,” said Pollack. “It’s relationship-building, family-building. Our staff really loves it, we truly do.”

Many factors make this type of family-style classroom service difficult to replicate, particularly cost. Wiggins estimates it would take about $25,000 per campus to replicate this kind of service and notes the Garden Oaks program is still a work in progress. In addition to needing more equipment—specifically, a dishwasher to accommodate the serving bowls and plates used for family-style service—they are still searching for utensils that are easier for tiny hands.

“Dr. Pollack and I had a real collaboration,” said Wiggins. “It was an investment—a lot of training, and an investment in equipment for that school—but it was in the best interest of the kids.”

“Our whole existence is adapting,” she said. “Taking what you have and making it work.”

Field Trip! An Urban Farm for HISD

Wiggins knew replicating her school garden plan from Detroit wouldn’t quite work for Houston ISD schools. In a district the size of Houston, a new approach to food education would be required. Though there are campuses growing school gardens, Wiggins is focused on developing a new K–8 urban agricultural center for HISD students.

“When kids get into high school they become consumers, but in the K–8 environment we can train the kids up,” she said. “We have a six-and-a-half acre piece of land the district gave us. It’s going to be an agricultural education center for K–8 where we’re going to grow crops, where kids can have field trips, interactive things where they can learn about food.”

Growing enough food to illustrate food concepts and do food tastings is harder than it sounds for a district the size of Houston ISD.

“In Detroit I couldn’t raise enough food for all the cafeterias,” said Wiggins. “I had reality hit me when we raised two-and-a-half acres of corn and I got half the district fed! And here’s the thing about when you go out to buy locally from a farmer—I can [take your entire harvest]! Then what about the next school district that wants to bring their kids the same food from that farm?”

The true value of the school garden is the educational value, said Wiggins. In the meantime you use local when you can and take advantage of the rest of your NSLP resources when you can’t.

“The Texas Department of Agriculture is very good,” she said. “The emphasis is on protein. We’re using more USDA foods like catfish— a Louisiana catfish. We’re using strawberries, and we get our apples through the Department of Defense using those contracts. We’re using agricultural products.”

Reflections: Houston (and Texas) on a Lunch Tray

The school garden is one way of teaching kids food literacy and food inclusion; new menu items are another. Reflecting the diversity of HISD’s student body on the lunch tray is a priority for Wiggins and her staff. It helps that Houston is a great food city, too.

“Everyone around here eats everyone else’s food, which actually makes it easy to educate the kids,” said Wiggins. “We put pupusas on the menu, and we just did a food show for parents at the Mandarin Immersion Magnet School and we’ll take that menu and introduce parts of it in other schools.”

And then there are the GOOD FOOD T-shirts. Wiggins had them made in a handful of languages spoken by families in the district to spark conversations about food literacy, and according to her they work—she’s been chatted up by a rental car agent, a flight attendant and a neighbor back home in Michigan.

“When someone says ‘GOOD FOOD’ I get a chance to talk about what we are doing with food inclusion, our work changing our menus, changing our lifestyle and making kids understand they have choices,” said Wiggins.

A Time Change

It’s possible that the biggest, most impactful change to school lunch we could advocate for has nothing to do with the food at all. What if we simply give kids more time to eat? After all, if a kid has to toss uneaten food to get back to class it hardly seems like it matters where it was grown. Making the meal a priority of the school day has the potential to change everything.

“We need to think about child nutrition programs as wraparound services that support academic achievement,” said Wiggins. “My access to kids and feeding kids is determined by a school calendar, by minutes of instruction, the number of buses in the driveway, the teacher breaks.

“After all of that they decide ‘lunch starts at 10:15am.’ So where is the priority? Kids are at the mercy of adults, and these are the things I think parents need to know school lunch depends on. I think we should all ask why we get one hour for lunch and our kids get 20 minutes.”