My Gram's Blue Apron

What our grandmothers were telling us at the table

The hotel kitchen is a mess. It’s become the gathering spot for a midweek family meal for the friends I’ve made since being transplanted from Houston to this lonely place. On the table tonight is Bok Choy Soup. Ten minutes down the road in Scotland, Texas, my friends Tommy and Denise grow vegetables for a living, providing an endless supply of ingredients for my table here.

I left my family on my paternal grandparents’ land west of Houston a couple years ago for Archer City to help run a historic brick hotel built in 1928, which in its modern life has become a small-town stop for writing workshops, hunters, and book lovers visiting Larry McMurtry’s still-open bookstore, Booked Up. I came because there was an opportunity to rebuild a high school arts education program in a small town. But since I’ve come, my school has turned out to be the kitchen and my teachers the grandmothers in my life and what they have to say.

My mom’s mother, Minna Head Harding, was born in 1905 on a farm in Coleman County, out in west Texas. The oldest girl of four children, she took up her spoon at the stove by the age of 6, the year her mother died. She then raised and fed her own five children as a farmer’s wife, only moving to town for all of its conveniences in her final years.

My dad’s mother, Priscilla Houston Menke, was born a town girl in 1918 in Bangor, Maine, the oldest daughter of a school superintendent. She left home to get what her mother always wanted: a college degree. She then joined the Navy, married a Texan, saw the world and found herself marooned in a sea of cattle an hour outside of Houston, settling on her husband’s ranch land after World War II to raise a family. She became my closest grandparent, the one who drove me to piano lessons, who taught me to play checkers, the one I remember planning for big parties at her kitchen typewriter and cooking Jell-O with at the stove.

Her oldest granddaughter, a product of the 1970s, I came into the kitchen late in life, realizing only last summer that her blue apron has become my most treasured possession. I inherited her recipe box full of typed recipes and a few stray party menus and the apron when she died 11 years ago, but it wasn’t until I moved here, back to a small town, that I began looking into that box and wearing that apron.

After college I traveled the world, settled into city life, never married, didn’t have kids. Like many young people, some of my decisions were reactionary to the ones I’d been raised around. But mostly I was just eager to use my freedom to its limits, as she had. I suppose had I come to the kitchen any other way it would have felt a limitation. I had choices and I’m happy with the way I used them, but until I put the apron on, I didn’t really know who I was.

Priscilla Houston Menke lived across the pasture from me growing up. I remember watching the ladies park their shiny sedans out front along her long circle drive for the parties she’d host in her two-story , her parlor set for bridge. I remember summers getting to go to Gram’s house for lunch on her back porch with Pop and sit in a big wooden armchair with my feet dangling over the brick red tile.

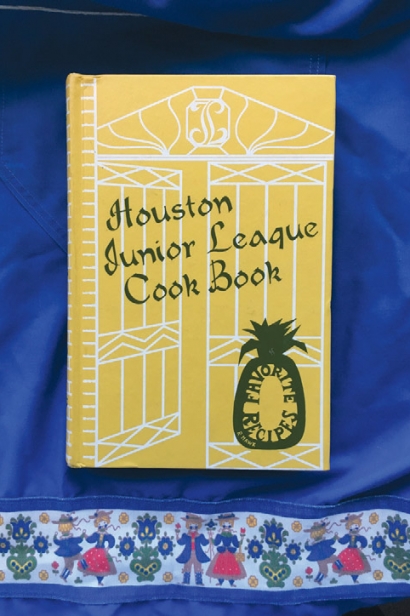

I’ve been running through her old typed recipes for a year now, seeing her penmanship again, laughing at her priorities, such a small window into a private world I never knew. I made a Hilltop Farms Brown Bread recipe the other day, an East Texas restaurant and herb garden made famous to Houston by its creator, the late Madalene Hill. Tonight, I pull out one typed “Rosa Lee’s cornbread” to go with this thrown-together Asian-inspired soup, to keep it interesting. Just holding the card made me wish I’d had the chance to stand with her in my grandmother’s kitchen while she worked. Rosa Lee had a reputation in the county as one of the best cooks. But today I know nothing else about her.

Making her cornbread, I wondered what their relationship was like over the years, a New England transplant and a Southern cook, cultural opposites, side by side. Gram’s recipe box suggests she both knew how to cook anything she set her mind to and to let an expert take over when she saw one. I just wonder if they talked much together about the food. What did it mean to them both? Were they products of their social structure, two rural ladies feeding their communities? Were they friends? Gram was, after all, an outsider with a Maine accent and known for being proper but friendly and capable of saying anything. I wonder if they said things that never left that kitchen. Gram had seen Duke Ellington play in New York City. I wonder if they ever talked about music, if Rosa Lee ever heard her playing songs on the piano in the middle of the day. Maybe she did. I wonder if they ever talked much at all, or if one of them didn’t feel free to. I’m thinking of all this as I mix the recipe and pour it into the cast-iron pan.

I spend my evenings now digging into the box of Gram’s photos and letters, pulling out a set of snapshots, seeing the love she had for me for the first time through the eye of her camera. Every time I am in the kitchen cooking, I think about how much fun it is getting to know this part of me that I had let die. What do we young people know anymore? I suppose it’s been an even trade: new recipes, old aprons, but I get more of who they were and what they were saying only in the doing. I guess that’s why I cook: to do what only gets done at a table.

I look down at the soup and cornbread. A handful of people crowd around, informal enough as it is. There are no napkins; the butter for the cornbread sits as the centerpiece, in its wrapper with a knife. We drain the bowls, talk the day out and head back into the rain to our houses.