Sowing the Grains of Change

How a Japanese immigrant stirred the pot in a creole city

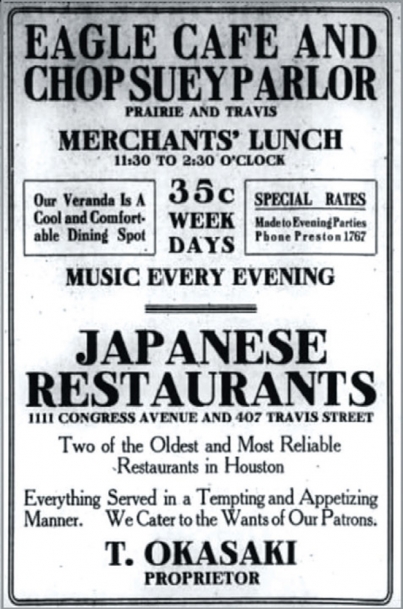

On the evening of Saturday, August 12, 1916, as ceiling fans whirred and a summer breeze blew through the second-floor windows, Houston police raided the fern- and palm-adorned Eagle Café and Chop Suey Parlor, at Prairie and Travis. As the cops entered the dining room, house band Frank J. Franc and his Futurist Sextet was playing a syncopated song while swanky diners slurped crab gumbo and briny Blue Point oysters before enjoying spring lamb with caper sauce, tenderloin trout with tartar sauce, or a toothsome chop suey. Led by District Attorney John Crooker, the police arrested the well-respected Japanese proprietor and serial entrepreneur Tsunekichi “Tom Brown” Okasaki for allegedly selling liquor without a license.

Even then, a century ago, one needed to look no further than its restaurants to see that Houston was and would remain a city of immigrants.

In 1888, Okasaki had emigrated from Japan’s Okayama Prefecture. It’s not clear when he arrived in Houston but by the late 1890s he had adopted an Anglo-sounding name and opened Tom Brown’s Japanese Restaurant, at 1111 Congress, directly across the gravel street from the Harris County Courthouse. He served “American” food to area workers and Japanese food to a small but growing Japanese community.

When Okasaki arrived in the Bayou City, it was already experiencing the exponential growth that has characterized the city throughout its history. The city’s population had grown from 2,396 in 1850 to 44,663 in 1900. Then, like now, the growth was driven by international immigration and domestic migration.

Most of Houston’s early residents were Anglo immigrants from the United States and the enslaved Africans they forced to move with them. By 1900, German immigration, which had been significant between 1836 and 1860, had slowed but German settlers and their descendants were well established. Many were prominent businessmen, including the Prussian immigrants who ran the grocery store on the first floor of the Eagle Café building (now home to El Big Bad) from around 1877 to 1913 (see sidebar). Other Germans were growing vegetables, cultivating rice and raising dairy cattle in northern Harris County and along Brays Bayou, where the Texas Medical Center and Meyerland are today.

Around the 1880s, Italian immigrants, primarily farmers from southern Italy and Sicily, began arriving. By the early 1900s, many were operating truck farms in what is now the Galleria area, while others were growing vegetables along Little York Road and operating grocery stores throughout the city. Around this same time, immigrants from Ottoman Syria (modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and northwest Iraq) began settling in the Near Northside and the Second Ward. Many became key players in wholesale and retail produce and in the grocery business.

They were joined by Russian and Eastern European Jews escaping the pogroms, many of whom also entered the produce and grocery businesses. Also arriving were Brits, Norwegians, Swedes, Tejanos and Tejanas from across Texas, African Americans from rural Texas and Louisiana and Midwesterners looking for jobs in the railroad and cotton industries; a handful of Chinese who in spite of legal restrictions against their immigration established several restaurants and small businesses in downtown Houston; and, starting in the early 1900s, Mexicans, many escaping the Mexican Revolution.

This is the milieu in which Okasaki found himself operating his first restaurant: a burgeoning port city that was a major hub for railroads and cotton, which, even though it was segregated and primarily run by a white majority, was already attracting and relying on immigrants.

In 1903, Houston civic leaders, executives of Southern Pacific Railroad and the Japanese consulate general in New York encouraged Japanese lawyer, politician and college president Seito Saibara to recruit prominent Japanese to establish rice farms on the fertile coastal plains between Houston and Beaumont.

Rice had been grown commercially in Texas since at least 1836. At first, relying primarily on slave labor and primitive growing methods, early Texas rice farmers had limited success. But with the introduction of new technologies and improved milling and transportation infrastructures, Texas rice production was on the rise by the 1880s and Houston elites saw an opportunity to make the area a leader in rice cultivation.

When the Japanese immigrants arrived, they brought with them experts in rice farming and, more importantly, a Japanese variety of rice known as Shinriki (or “power of god”), which outperformed other varieties grown on the Gulf Coast, helping to temporarily transform the area into a major rice center.These new Japanese-Houstonians found their way to Okasaki’s restaurant as customers and as employees. One of them was American-educated, socialist Sen Katayama (née Sugataro Yabuki), who worked at the restaurant as a cook and waiter. Inspired by the success of Saibara, Okasaki and Katayama set out to establish their own rice-growing colony. In 1905, the two went to Japan to recruit workers and to secure $100,000 from Katayama’s wealthy childhood friend Iwasaki Seiki

chi, whose uncle was a co-founder of Mitsubishi. With those funds, they purchased 10,200 acres in Live Oak and McMullen counties and Katayama began work as managing director of the project. By 1906, however, Katayama’s mismanagement and socialist leanings caused a bitter rift between him and Okasaki. The partnership soon dissolved and Katayama returned to Japan, where he co-founded Japan’s Communist party.

Fortunately, the other Japanese rice farmers were thriving and Okasaki and the Bayou City benefited. In April 1910, the Houston Post hailed Houston as “one of the best restaurant towns in the South,” crediting Okasaki, an immigrant, as one key to the successful dining scene. By then, he had opened a second branch of his popular Japanese Restaurant at 407 Travis and a retail shop, the Japanese Art and Tea Company at 709 Main Street. This success spurred him to open yet another restaurant.

On Saturday, April 19, 1913, Eagle Café and Chop Suey Parlor opened at the northeast corner of Travis and Prairie. The Houston Post breathlessly declared “Suey famine ended” and called Okasaki a “genius.” Chop suey, an American-Chinese dish whose exact origin is the subject of competing myths, began appearing on U.S. menus in the second half of the 1800s when the cooking of Chinese immigrants encountered the Anglo-American palate. In the early 1900s, even as the Chinese faced severe discrimination, chop suey was becoming a full-blown craze. By 1910, New York alone had close to 100 restaurants serving the dish.

In may be coincidence that Okasaki choose the patriotic-sounding “Eagle Café “ over “Japanese Restaurant” in the same year California passed an Alien Land Law, which prohibited Asians from owning or possessing long-term leases on agricultural land. But it seems clear he saw an opportunity to capitalize on the chop suey rage.

He hired a German immigrant, Carl Ester, who had been the head waiter at the Grunewald Hotel in New Orleans, to manage the wait staff and hired British immigrant Eustace Lancelot Crudge, who had spent years working in Midwestern restaurants, as the chef to manage what the Houston Post assumed were Chinese cooks.

Ninety-nine years before John T. Edge called Houston “Mutt City,” a Japanese entrepreneur hired a German head waiter and a British chef to serve Houstonians a menu of chop suey (an Americanized take on Chinese food), along with gumbo (a blend of African, Indigenous and French cuisines). standard “American” fare of that time (oysters, lamb, wild game and fish, turkey, potatoes, asparagus, orange sherbet) and a handful of Chinese and Japanese dishes.

Though ongoing discrimination and new state and federal legal restrictions would slow immigration to Houston between the 1920s and the 1960s, Okasaki and his fellow immigrants had helped lay the groundwork for the multicultural city Houston would become.