A Globe in Shades of Orange

Oranges remind me of summer. Maybe it’s because the orange spheres look like a child’s conception of the sun. Maybe it’s the years of seeing orange juice ads promoting a sunny, semi-tropical Floridian wonderland.

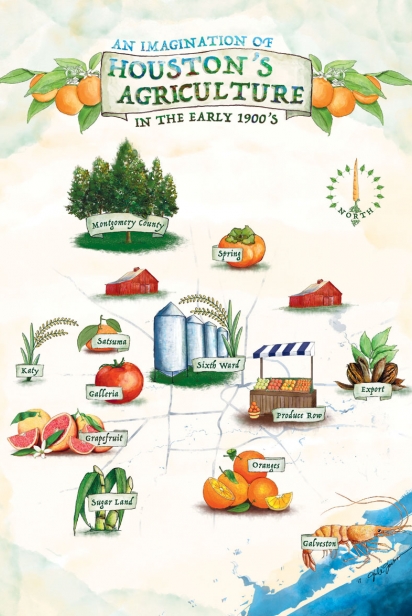

But oranges, and other citrus, are actually not a summer fruit—a fact I didn’t fully understand until I began shopping at Houston’s farmers markets, where from late October to March, if we are lucky, you can find a vast array of locally grown citrus: Meyer lemons, Republic of Texas oranges, Ruby Red grapefruits, Ujukitsus, Cara Cara Pink Navels, Satsumas, Moro blood oranges, pomelo, Buddha’s Hand and many others.

Citrus, as you can tell, is a prodigious cross pollinator. Most citrus varieties are hybrids derived from three species: citron (Citrus medica), mandarin (Citrus reticulata) and pomelo (Citrus maxima). The grapefruit (Citrus paradisi)—the citrus Texas is best known for— is a cross between pomelo and sweet orange, which is itself a cross between pomelo and mandarin.

In addition, one other ancient species, small-flowered papeda (Citrus micrantha) has lent its genes to the citrus family. Persian lime—the fulcrum of Houston’s favorite patio drink—is a cross between a Key lime (a small-flowered papeda and citron cross) and lemon (citron crossed with sour orange, which is a pomelo and mandarin cross)—such is the complex, incestuous world of citrus.

Citrus is also an ancient and prodigious traveler. The exact origin of citrus, like most plants and foods, is all but impossible, to pinpoint. But most genetic and archeological evidence points to citrus first growing, being eaten and cultivated in tropical and subtropical Southeast Asia. According to National Geographic, fossils found in the Yunnan province of China indicate that citrus has existed there for approximately seven million years. Citrus eventually migrated around the world. Based on seeds discovered in the excavation of Mesopotamian sites, the citron had arrived in the cradle of civilization by 4000 BCE.

War, religion and trade fueled many of citrus’s subsequent journeys. In 326 BCE, Alexander the Great invaded India, where citrus had long been revered. One of the earliest mentions of citrus is in the Vajasaneyi Samhita, a sacred Vedic text written in Sanskrit around 800 BCE. The importance of citrus was not lost on Alexander’s officials, who brought citron, which in India symbolized prosperity, back to Greece. Greeks then helped introduce citron to Palestine, Turkey and North Africa.

Around that time, citron became important to Judaism, especially during Sukkot, a harvest celebration. There are competing theories about when the Jewish people first encountered citron, which they call etrog. Some speculate that Alexandrian Greeks introduced it to them; others that exiled Jews brought it from Egypt; and some suggest they first encountered citron in Persia, where it had been grown since at least 500 BCE. No matter when the first encounter occurred, the Jewish diaspora was instrumental in spreading citron throughout the Mediterranean, Europe and the New World.

The Muslim world filled the citrus void left by the collapse of the Roman Empire, where citron and lemon were grown as prized luxury goods. “It is clear that Muslim traders played a crucial role in the dispersal of cultivated citrus in Northern Africa and Southern Europe,” archaeobotanist Dafna Langgut told Popular Archeology. Sour orange, pomelo and limes traveled the Silk Road and Spice Routes to the Middle East. By 1000 CE, Muslims were growing them on the Iberian Peninsula.

The Spanish and the Portuguese used the knowledge of citrus learned from Muslims to introduce citrus—primarily oranges and limes—to the New World. In the early 1500s, the first Portuguese colonist to reach Brazil planted citrus trees. Forcing enslaved Africans to do the work, they established a thriving orange industry that is today the largest in the world. In 2013, Brazil produced 35.6 million tons of oranges, over twice what the United States, the number two producer, grew. Spain, the number six grower today, in the early 1500s introduced citrus to Florida and Mexico, the number five producer.

Not surprisingly, it’s unclear when citrus was first introduced to Texas. But one of the first and more important recorded plantings occurred in 1871 in Hidalgo County. Carlota Vela, the daughter of Mexican nationals who immigrated to Texas in 1857, was given orange seedlings by a traveling priest. She planted them on Laguna Seca Ranch, the land her parents bought after her father worked for several years as a ranch foreman.

Though these initial plantings weren’t commercially successful— the rootstock wasn’t right for the Valley’s soil—they did kick off a period of experimentation that led to commercial success. Throughout the 1880s and ’90s growers established citrus orchards along the Texas Gulf Coast. But freezes in 1899 and 1911, just as citrus was gaining popularity, were major setbacks for many Gulf Coast growers.

The problem was serious enough that on April 12, 1912, the Texas Department of Agriculture and several statewide horticulture organizations held a joint meeting in Houston to discuss the state of Texas citrus. With J.W. Carson, who managed Harris County’s experimental, demonstration farm, presiding, J.W. Canada of the Texas Citrus Fruit Growers Association reported on his tour of the state’s citrus orchards. Of the 5,000 acres of citrus growing in 1911, approximately 80% was affected by the freeze and all nursery stock was lost. Tsukasa Kiyono, who immigrated from Japan in 1907 with the intention of starting a rice farm, lost his orchard in League City. He never recovered, moving to Mobile, Alabama, where he became a successful nurseryman.

Despite the devastation, attendees were still optimistic about Texas citrus. Speakers touted the high per-acre returns and shared strategies for surviving the next freeze: using 150 oil heaters per acre, planting trees closer together, establishing windbreaks.

For some, the optimism paid off. By 1940, Galveston County, the biggest citrus producer in the Houston area, was harvesting approximately 50 tons of mandarins annually. But Houston-area’s growers were never as successful as some had hoped—Dairy Ashford Road was once called Addicks-Satsuma because of the promising orange orchards planted in the Cypress area.

The optimism really paid off for the Rio Grande Valley, especially in Cameron and Hidalgo Counties. By 1940, Hidalgo County, the most productive citrus growing region in the state, harvested 79,657 tons of mandarins, 50,000 tons of other orange varieties, a thousand tons of lemons, several tons of limes and 390,829 tons of grapefruits.

Houston played a key role in the Valley’s success, providing both consumers and a distribution hub, especially for grapefruit. In the early 1910s, the Houston Post was generating interest by regularly running citrus recipes geared toward housewives. A 1912 article featured a recipe for a new jelly: grapefruit jelly, which was paired with potted chicken. A 1913 piece recommended marinating your grapefruit in sherry or apricot brandy. A 1914 column suggested several savory grapefruit salads and stuffing green peppers with a mixture of grapefruit, celery, walnuts and mayonnaise.

At first, most of the citrus was being shipped from California and Florida. But, on October 27, 1915, Houston received its first shipment of Hidalgo County grapefruit. The Houston Post reported that Houston wholesaler Desel-Boettcher had purchased the “entire output” of McAllen-based packer A.P. Hall at $5 a box, which was $1.50 cheaper than Florida grapefruits.

By the 1920s, Sig “Grapefruit Kid” Frucht, the son of Jewish immigrants from Austria, was importing train-car loads of Valley grapefruits both for Houston consumers and to sell wherever Houston’s extensive rail system could ship them. Throughout the 1920s, Seald Sweet, one of Florida’s major citrus companies, felt its market share was threatened enough that it regularly ran advertorials in the Houston Post highlighting the benefits of their brand.

In 1929, a Valley grower discovered a red grapefruit growing on a pink grapefruit tree he had imported from Florida. In 1934, it was patented as the Ruby Red, the variety that pushed the Texas grapefruit business to its peak in the mid-1950s, when 120,000 acres of citrus trees were in production.

This success had its dark side. Growing, harvesting and packing citrus required hours of backbreaking manual labor that was provided by underpaid and exploited Mexicans and Mexican- Americans. By 1966, the workers’ conditions were so bad that the Harris County Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations sent several hundred people to the Valley to participate in a minimum wage march that was advocating for a $1.25-per-hour wage and growers’ recognition of the United Farm Workers Association.

Though the Texas citrus business has shrunk and is now dealing with citrus greening disease, it is still thriving and small Houston-area growers are making a resurgence, providing a wide variety of citrus to area farmers markets.

As you enjoy that variety—slicing into a bright, tart Ruby Red or juicing a sweet Republic of Texas—remember you are partaking in thousands of years of globe-spanning history that includes Chinese emperors, ancient Greek soldiers, Jewish rabbis, Islamic traders, Spanish explorers and Mexican immigrants. It turns out that spherical orange is more like our fragile planet than the sun.