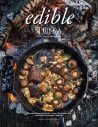

Fall is for Foraging

Hunting and gathering nutrient-dense wild edibles throughout autumn

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 14, 2020

Lacing through the oak branches overhead—laden with clusters of acorns—bunches of Muscadine grapes hang tantalizingly out of reach. Once ripe, both nuts and fruits will tumble down and I’ll do my best to beat the squirrels to ’em. Farther afield, prickly pear tunas, chiles pequins, Mexican plums and persimmons will reach maturity and slip from their stems like an array of multihued gems.

Nature saves her most nutrient-rich foods for fall, when wildlife—and our ancestors—can store them away for the harsher months ahead. While many animals do this in the form of body fat, we have other options available to us, such as canning, drying, and preserving this embarrassment of riches.

Whether you’re an experienced forager or just starting out, Houstonians are blessed, indeed, to have arguably one of the nation’s preeminent foraging experts in our midst: Mark Vorderbruggen, best-known to foragers by his alter-ego handle, Merriwether. His Facebook page, Merriwethers Foraging Texas, recently topped 25,000 followers, testament to his popularity.

“Seedlings,” as he fondly calls his foraging followers, use his content-rich website foragingtexas.com as a “go-to” source for wild plant information. You can also take one of the spectacularly fun and informative classes listed there, as did I. His first book, Idiot’s Guide: Foraging, was published in 2016.

“I own lots of foraging books,” he says, “so I examined what I thought were their failings so as not make the same mistakes, and set my goal as writing the best foraging book out there.”

Merriwether’s foray into foraging instruction began in 2008, when the Houston Arboretum contacted him to lead foraging walks, which immediately became wildly popular. He’s now expanded to giving classes around the state, as well, with dates and times listed on his website.

“I didn’t start foraging,” says Merriwether, when I ask at what age he began his fascination with native plants. “Both of my parents grew up in Depression-era Minnesota, and picking dandelion greens with my mother is among my earliest memories. Harvesting wild foods was a way of life for us.”

The lad picking wild greens would go on to earn a degree in organic chemistry from South Dakota State University, where his hiking buddies (somewhat derisively, he says ruefully) nicknamed him “Meriwether” for his fascination with plants. “I liked it, though,” he says, eyes a-twinkle. “Meriwether Lewis makes a fine role model.” The double ‘R’ spelling is Vorderbruggen’s personal stamp, and befits his jovial demeanor.

He later completed his master’s and doctorate in organic chemistry at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in upstate New York, which in the late ’90s landed him a job in Houston. He defers mentioning his employer’s name, saying euphemistically: “My job is to find environmentally friendly, plant-based solutions for traditional oil field chemicals.”

Merriwether counts acorns, American beautyberries and wild Mexican plum among the forageables he most looks forward to in fall. “Making acorn flour is a lot of work,” he says, “but made much easier using the cold-process method that Hank Shaw describes on his Hunter•Angler•Gardener•Cook website. Beautyberries make excellent jelly and wine and I make sourdough starter from the wild yeast on the plums.”

From Field to Plate

Creative chefs around Houston relish both the epicurean and environmental aspects of foraging. Chef German Mosquera, who with partner Brandon Gregoire runs the underground supper club Dig & Serve, loves to supplement their impeccably fresh local produce with foraged greens.

“In the fall, I especially like wild onion, purslane and Turk’s cap,” Mosquera says. “I’ll infuse vinaigrettes with Turk’s cap blossoms, or use them in marinades much as you would hibiscus blossoms (roselles). The leaves can be sautéed, stir-fried or steamed and the berries are edible as well. Foraging increases my awareness of what’s practically underfoot—even in the concrete jungle.”

Chef Erin Smith, a native Houstonian and co-owenr of Feges BBQ, became interested in foraging about a decade ago, fueled by others who were passionate about wild edibles and happy to teach her. “It really opens your eyes to what’s right in front of you that’s edible,” she says, “and when it’s at the height of freshness.”

Foraging bring immediacy to a chef ’s repertoire, as these wild ingredients are ephemeral, becoming available for only a short time. Smith counts chanterelles among her favorite fall forageables, but warns that they—as do many other mushrooms—have a deadly doppelgänger so positive identification is imperative so as not to confuse one with its toxic look-alikes.

“Going afield with an experienced mycologist is best,” she says. She’ll also be poking around fallen oaks for turkey tail mushrooms and plucking delicate wood ear mushrooms. And while she will use some of these to season stocks, most—especially the worth-their-weight-in-gold chanterelles—she prefers to simply sauté in a bit of butter. Be forewarned that the bases of oak trees, often fertile ground for chanterelles, are also popular with copperhead snakes, so wear boots and probe around the base of the tree with a stick so as not to have an unpleasant encounter.

And me? The Texas State Wild Pepper, the chile pequin, tops my September list. Also called chiltepins, turkey peppers or bird peppers, these miniscule fireballs pack a volcanic punch—up to 40 times hotter than jalapeños. Seek the shrubs edging woodsy areas and use the smoky, citrusy peppers to make salsas, to infuse vinegar, to flavor soups and stews, or dehydrate them for year-round use. I’ll also be wading into the cactus flats for ruby-red prickly pear tunas for prickly pear jelly, marmalade, syrup … and prickly pear margaritas.

Not since Euell Gibbons’ landmark Stalking the Wild Asparagus debuted in 1962 has foraging found such a fervent following, so step outdoors and look around you for delectable fall edibles.

“It changes the way you look at things,” says Chef Smith. “Once you open your eyes to foraging, you find interesting edible plants all around you.”

FORAGING ETIQUETTE

With more than 95% of Texas being privately owned, and foraging prohibited on most public lands including all state and national parks, one might wonder where to begin foraging. Often, the answer is as close as your own backyard—or a neighbor’s. Being of the “it never hurts to ask” mindset myself, I’ve knocked on a few doors to request permission to forage, and haven’t been turned down once. Use Merriwether’s “Four Rs of Foraging Ethics” as your guide:

FORAGING ETHICS

1.) Respect the law. You must have permission from the property owner to collect plant matter. To forage without permission is considered stealing and you can be arrested. Most state and federal lands prohibit gathering plants except in survival situations.

2.) Respect the land. Leave no trace. Fill your holes, pack out your garbage (and garbage left by others), don’t hack/slash/ smash/burn your way through nature. Don’t harvest a plant if there are just a few around.

3.) Respect the plant. Please harvest sustainably so that there will be plenty of plants year after year. Also, don’t strip all the leaves from one plant, just take one shoot or two to three leaves from each of many plants. Minimize damage to the plants by cutting leaves off the plant with a sharp knife or shears rather than tearing them off. Harvest inner bark using long, thin vertical strips on one side of the tree, do not cut a ring all around the tree, which will kill it. Sterilize your cutting tools with alcohol or bleach to prevent transfer of diseases.

4.) Respect yourself. Please positively identify any plant before eating it. Eating the wrong plant can lead to illness or, in rare circumstances, even death. Also be aware of any environmental hazards in your foraging location such as snakes, bears or chemical hazards from old oil fields, roadways, lead paint around old buildings or areas subject to flooding from sewers.